Many high-profile political cases in Russia in 2022-2023 have been initiated based on informant reports. For example, due to such reports, musician Sasha Skochilenko and amateur archaeologist Oleg Belousov were sentenced to 7 and 5.5 years in prison, respectively.

To what extent does the current wave of political repression rely on denunciations, and who writes them? Paper examined court cases in St. Petersburg, spoke with the informants themselves, and those who researched them.

Read about why denunciations cannot be called a mass practice, how informants explain their motivation, how they choose victims, and what part of political cases is based on informant reports.

Table of Contents:

1. In St. Petersburg, a small portion of political cases has been initiated based on informant reports.

2. Denunciations are often written not by ordinary citizens but by law enforcers.

3. The most active informant organization in Russia is the League of the Safe Internet.

4. One of the main targets for serial informants is “LGBT content.”

5. Informants believe that they are cleansing the internet of harmful content and protecting children from it.

6. Serial informers can submit up to 1000 reports per year.

In March 2022, Russia enacted laws allowing prosecution for statements online and reposts on social media. There is a need for individuals who find prohibited posts and report them to initiate such cases. That’s how the theme of informants arose.

On March 21, the A Just Russia – For Truth political party already created a website for collecting and submitting reports to the Investigative Committee of Russia against the “vermin” of the state. In various regions, United Russia and other movements launched bots for informer reports. A parody service named My Informant emerged. News of the “revival of snitching” began to surface, with reports indicating that Russians had started to write denunciations en masse.

However, the data collected by Paper does not confirm this.

In St. Petersburg, a small portion of political cases has been initiated based on informant reports

According to our calculations, relying on publications from the press service of the courts in St. Petersburg, from March 2022 to November 30, 2023, 110 politically motivated cases were initiated in St. Petersburg. Among them, only in 18 cases (16%), there is information that the cases were based on informant reports.

In the remaining cases, the cases were initiated based on surveillance camera footage (inscriptions on walls etc.), or the police noticed a violation on the spot, or the source of information about the violation was not disclosed.

What do we consider politically motivated cases? ↓

We include the following criminal articles in the category of politically motivated crimes: spreading fake news about the army – article 207.3 of the Criminal Code of Russia; hooliganism for political reasons – article 213 (pt.2) of the Criminal Code of Russia; calls for terrorism – article 205.2 of the Criminal Code of Russia; calls for extremism – article 280 of the Criminal Code of Russia; incitement of hatred and enmity – article 282 of the Criminal Code of Russia; organization of extremist activities – article 282.2 of the Criminal Code of Russia; insulting the believers’ feelings – article 148 of the Criminal Code of Russia.

The list includes also several administrative articles: discrediting the Russian army – article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; incitement of hatred and enmity – article 20.3.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; demonstrating Nazi symbols – article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; violation of the legislation on “foreign agents” – article 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; some cases of minor hooliganism – article 20.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; organizing a rally – article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; abuse of freedom of mass information – article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; violation of the procedure for disseminating media – article 13.21 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; violation of military accounting rules – article 21.5 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; failure to notify the draft board – article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; “LGBT propaganda” – article 6.21 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia; “LGBT propaganda” among minors – article 6.21.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of Russia.

Anthropologist Alexandra Arkhipova, in a conversation with Paper, suggested that there might be more informant reports, but their presence in a case is not always mentioned. This can be accurately determined only from the text of the verdicts, and they are not present in all cases.

“We have a database of cases under administrative article 20.3.3 and the criminal article 207.3. There is a subdivision ‘for oral statements’—almost 500 cases out of 6900. I assume that all of them are definitely about informant reports. In other cases, it is difficult to get to the source because it is not specified in the court decision.”

The government agencies themselves, such as Roskomnadzor or the prosecutor’s office, do not report how many informant reports they receive and how many of them are acted upon.

Cases in St. Petersburg initiated in consequence of denunciations:

- Sasha Skochilenko’s case—an elderly woman complained about Sasha’s anti-war act. Sasha was sentenced to seven years in prison.

- Oleg Belousov’s case—an acquaintance complained about anti-war comments on VK. Oleg was sentenced to 5.5 years in prison.

- Dmitry Denisov’s case—the police noticed a comment by a young man on the VK page where he referred to the Russian flag as the “flag of traitors.” Dmitry was fined 20,000 rubles.

- Vsevolod Korolev’s case—a person from St. Petersburg saw an anti-war post by Vsevolod on VK. The case is still under consideration.

Denunciations are often written not by ordinary citizens but by law enforcers

Out of the 18 informant reports identified by Paper in St. Petersburg since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the majority—12—were written by law enforcers: the Federal Security Service, the prosecutor’s office, and Centre E officers. The authors of the remaining two were Roskomnadzor and United Russia. Only four informant reports were written by ordinary citizens.

In almost all cases, law enforcers reported posts, messages, or comments on VK or Telegram. In these statements, the police and FSB officers saw “fake news” about the Russian army, its “discreditation”, incitement of hatred or enmity, as well as minor hooliganism.

According to the research findings of denunciation expert Alexandra Arkhipova as of February 2023, 44% of all administrative cases related to the “discrediting” of the Russian army on social media were specifically initiated based on statements made on VK.

VK is included in the “register of organizers of information dissemination” by Roskomnadzor. Since the enactment of the Yarovaya law in 2018, the company is obligated to store and, upon request, provide law enforcement with users’ personal data—including their correspondence, audio, and video messages.

The most active informant organization in Russia is the League of the Safe Internet

Individual Russian citizens write informant reports less frequently than entire movements or organizations. One of the most active is the League of the Safe Internet, led by senator Elena Mizulina’s daughter, Ekaterina.

The League was founded in 2011 with the support of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Communications, and the State Duma committee on family, women, and children. The League was founded by the St. Basil the Great Foundation, established in 2007 by Konstantin Malofeev, the owner of conservative TV channel Tsargrad. Kommersant reported in early 2022 that Malofeev had stopped supporting the League. It is known that the organization receives funding through presidential grants—for example, it won a grant for organizing the Safe Internet Month.

Initially, the organization fought against child pornography on the internet but later began to search for LGBT propaganda and extremism.

The League even created a separate youth movement called Cyber Druzhina to help its participants counteract “information warfare.” Whether the movement still exists is unknown—the last mention of it in the League’s social media was in 2022.

From the beginning of the previous year until November 30, 2023, the League of the Safe Internet, together with Ekaterina Mizulina, filed 3,915 informant reports—more than half of reports from all the Russian informants, as calculated by Paper. According to the organization's data, a total of 184.3 thousand online resources were blocked in Russia following its appeals.

Since 2021, Ekaterina Mizulina has been actively monitoring bloggers. In her Telegram channel, she recounts the complaints filed against bloggers promoting illegal online casinos, using drugs, transgender individuals, trash streamers, or rappers.

Whom did the League of the Safe Internet report in St. Petersburg:

- Founder of the rap battling platform RBL, Anton Zabaev—for justifying terrorism in a joke about the death of propagandist Vladlen Tatarsky.

- Yandex—due to the search engine providing 'Hitler' and 'war in Ukraine' as suggestions when searching for information about Vladimir Putin.

- Rapper Oxxxymiron—for “extremism” in his tracks.

- Blogger Anna Enina—for spreading “destructive content.”

- A female resident of St. Petersburg—for insulting participants of the war in Ukraine.

- Singer Eduard Charlotte—for “discrediting” the army and “insulting the feelings of believers” in social media posts.

Mizulina actively communicates with her readers, encouraging them to report any content they find illegal via the League of the Safe Internet website or Telegram bot. According to Ekaterina, the majority of complaints come from schoolchildren and their parents.

All messages are initially reviewed by the League employees. Then they are passed on to the organization's lawyers to prepare official statements to the Investigative Committee or the police.

One of the main targets for serial informants is “LGBT content”

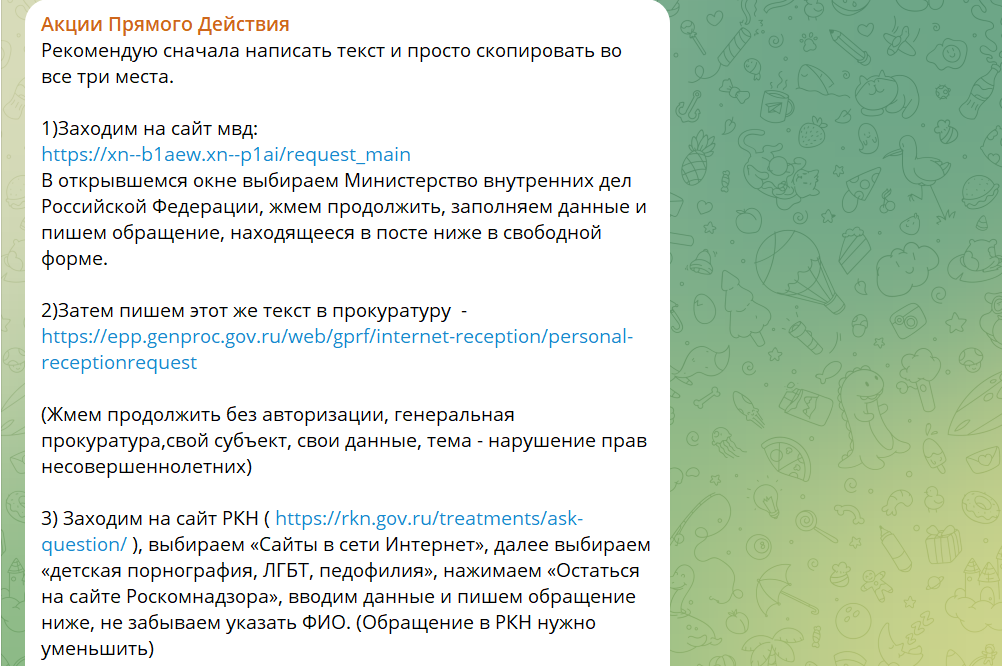

There are special movements actively searching for “LGBT propaganda” on the internet. Some of the most active include Direct Actions and the Anti-Libtard Organization.

Direct Actions have a Telegram channel where they publish information about their victims including personal data, and the texts of informant reports to be sent to the Investigative Committee. In addition to informant reports, movement members conduct spam attacks on social networks and phones of their victims.

Several times a month, new actions are posted in the channel. The writing of reports and social media spam is coordinated in a separate chat. From the beginning of 2022 to November 2023, movement participants organized 362 “actions,” as calculated by Paper.

In a special Telegram channel, members of Direct Actions publish reports of their attacks and the responses of authorities to their informant reports. According to the movement, 102 websites related to LGBT or opposition media were blocked as a result of their complaints. The informants also attempt to have teachers whom they consider LGBT individuals dismissed from schools and universities.

Direct Actions' claim responsibility for the blockage of the following resources:

- Website of the Groza media.

- VK page of the Side by Side film festival.

- Website of the LGBT initiative Center-T.

- Website of the LGBT initiative Vykhod.

- Fem Talks podcast on Yandex.Music.

- VK group Children 404 LGBT Teens.

The Anti-Libtard Organization operates using similar methods. The movement publishes posts with informant report texts and calls on subscribers to mass complain about LGBT resources. From the beginning of 2022 to November 2023, members of the organization initiated 313 actions involving the writing of informant reports, as calculated by Paper. According to the channel admin Alexander Kovalev, the movement successfully blocked approximately 150 resources in the 11 months of 2023.

In November, the Anti-Libtard Organization began to fight not only against LGBT individuals and resources but also against groups related to feminism, environmental activism, and voluntary childlessness. According to Alexander Kovalev, the movement is combating the “propaganda of voluntary human extinction.”

The exact duration of these movements' existence is unknown, as they periodically create new Telegram channels. Old ones are blocked due to frequent complaints.

Another Telegram channel, Multinational, publishes posts calling for informer reports on people of non-Russian ethnicity. They monitor cases of conflicts involving migrants and complain about them to the authorities.

The channel administrators regularly report on their work, submitting 12 to 29 complaints to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the prosecutor's office, and the Investigative Committee each month.

Informers believe they are cleansing the internet of harmful content and protecting children from it

Anthropologist and denunciations researcher Alexandra Arkhipova divides informers into three groups: they may do it for material, emotional, or moral gain. According to Arkhipova, ordinary citizens write most informer reports for emotional gain—when complainants ask law enforcement to resolve a personal conflict and want to harm their offender.

Informers of another type are convinced that they are defending the right values through their complaints.

“Moral entrepreneurs often justify their actions by protecting children,” Arkhipova gives an example. “Some of them want to destroy the enemy—make them silent. Other informers seek and destroy traces of the enemy's symbolic activity. Their goal is to draw a symbolic boundary between 'us' and 'them.'”

Members of the Direct Actions and the Anti-Libtard Organization expressed similar motivations in their conversation with Paper—they write informer reports from civil intentions and believe they make the internet and Russia safer and “cleaner.”

"I decided to engage primarily because Western society is slowly but surely falling into the abyss of all this debauchery [LGBT]. I find the normalization of these deviations (I cannot call otherwise transgenderism and the flaunting of numerous genders) unacceptable.

“Do I feel the benefit of all our appeals? Undoubtedly, yes, because thanks to this, we are slowly but surely achieving our main goal—completely displacing the propaganda of non-traditional relationships from the information field of our state.

“I have witnessed how such influence detrimentally affected some people in my circle who have undeveloped minds lacking critical thinking. Therefore, I decided that I must be involved in restricting the spread of such false ideas in our society.”

"I engage in this because [fighting against specific content] aligns with my worldview and beliefs.

“There is definitely a benefit from this—illegal content is being removed. It really gets on the nerves of liberal Westerners and sodomites—they swear, they are afraid, they call us 'fascists,' but they can't do anything about it. Russia is not a country for them; they have no business here.”

According to Paper’s sources, they try to write informant reports "as often as possible." The most active members of these movements, such as channel administrators, can, according to them, submit up to 50 reports per month.

Serial informers can submit up to 1000 reports per year

An example of an informer who explains their actions by financial interest is Anna Korobkova, who gained fame for writing letters to her victims.

In the spring of 2023, she wrote a denunciation on Alexandra Arkhipova for her comment on the TV Rain. After that, the anthropologist tried to contact the informer, and a correspondence ensued between them. The woman's name was disclosed by lawyer Kaloy Akhilgov, on whom she also wrote a denunciation.

Akhilgov explained that Korobkova, threatening to inform, offers experts to stop giving comments to "foreign agents” media. In letters to her victims, she explained that through informant reports, she tries to prevent a deterioration of her financial situation—from her point of view, this will happen if there is a change of power in Russia, and reparations have to be paid to Ukraine.

"The significance of informers like mine can be compared to the effect of using submarines to destroy enemy ships: the number of sunken enemy ships was always insignificant, but the fear of a possible attack forced the enemy to reduce the number of voyages.

“The informer's task is the same—to create an atmosphere of fear, in which any commentator in a ‘foreign agent’ media begins to wonder whether they will be reported to their employer or authorities. As a result, scientists begin to refuse to appear on the TV Rain, for example. This weakens TV Rain, which relies on donations, and ultimately leads to incorrect forecasts, a drop in viewership, and, eventually, the closure of the ‘foreign agent’ media.”

As Anna Korobkova told Paper in a letter, in the first year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, she alone wrote 764 denunciations. And from January to November 2023, she wrote another 783 denunciations.

Our investigation shows that despite the infrastructure created for reporting, it is primarily not ordinary citizens who write informant reports, but serial informers. These are several public movements, the main targets of which are bloggers and ordinary social media users, the independent media, and initiatives assisting LGBT individuals.

A significant portion of the denunciations are written by law enforcers. In St. Petersburg, it is their complaints that most often lead to the initiation of political cases.

Law enforcers were also the main authors of denunciations during the Great Terror, claims Mikhail Sheinker, an archivist-researcher of the Last Address initiative. "Throughout the Soviet times, there was always a wide network of confidential informants, ‘secret agents’, but for them, complaints were not denunciations but their service," he reminds.

"Sergei Dovlatov's expression that ordinary citizens themselves wrote several million denunciations is incorrect. By exaggerating the significance of denunciations, we shift the blame from the state to private individuals."

Что еще почитать:

- “Paper leaflets are probably worth less”. Interview with the woman whose complaint led to Skochilenko’s arrest

- We Asked Teachers How Propaganda Affects Studies and What Teenagers Think. Here are Four Observations on How Schools are Slowing Down Patriotic Initiatives